This is the story of a data model which has been design up-front. It was one of the first implementation tasks done in a new project. With the least knowledge (begin of the project), we tried to figure out the domain.

How it started

In the last project I was working on, we struggled a lot with our data model. The task was to replace an old product service with a new one. The old system has grown over time, was hard to maintain and the guys who made it have been gone a long time ago. The usual story. Our task was to replace the system with a new one, based on state-of-the-art technology, ready for the future. Also, the usual story.

So we began to think about an architecture and to develop our data model. We spoke with domain experts, explored the old code and made meetings with everyone who would be using our system.

Often, this kind of research was going like this:

Developer: “Hey, how’s this category thing working?”

Stakeholder: “Ah, that’s simple. A product can be in exactly one category.”

Developer: “Cool. Anything else?”

Stakeholder: “Well, we want to change this. A product should be in one or more categories in the future.”

Developer: “O.K., when should this feature be ready? Do you have a deadline?”

Stakeholder: “Oh no. We just talked about it. Maybe in a couple of months? Maybe next year?”

Or like this:

Developer: “Hey, how’s that brand thing working?”

Stakeholder: “That’s simple. Every product has a brand.”

Developer: “Cool. Anything else?”

Stakeholder: “Well, we want to change this. Every brand should get an address and a sub-brand, too.”

Developer: “O.K., so where will we get that data from?”

Stakeholder: “We don’t have it yet. Maybe we will get it from that new logistics system.”

Developer: “When is this system coming?”

Domain Expert: “No idea. We’re talking about it since a year and half, but we don’t have time for that now.”

Two worlds

After a couple of those discussions, we knew that we were living in two worlds.

There was a simple and very concrete world where things were clear. A product was part of a single category and a brand was just a name. It’s also the world of the current system, it’s how things are working right now.

{

"sku": "B-123456",

"name": "Coca-Cola",

"category": "BEVERAGES",

"brand": "The Coca-Cola Company"

}

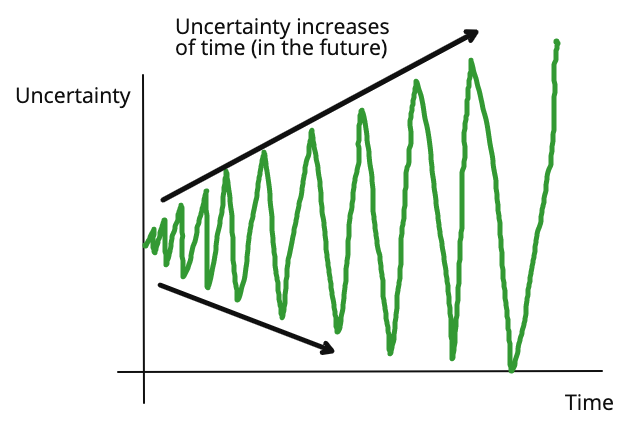

And there was a world of the future. A world of uncertainty and open questions, but also a world which will come. At least sometime.

{

"sku": "B-123456",

"name": "Coca-Cola",

"category": ["BEVERAGES", "LIMONADES"],

"brand": {

"name": "The Coca-Cola Company",

"subbrand": null,

"address": {

"name": "The Coca-Cola Company",

"city": "Atlanta"

}

}

}

So which way we should go? The way of a simple data model which only fits the current needs? Or the way of a data model which is extensible and ready to tackle the future?

The future

Of course, the tempting solution is the generic data model which is “future ready”. But the problem is the uncertainty this model is build around.

Let’s imagine that we’ve implemented a list of categories instead of a single one.

Instead of "category": "BEVERAGES" we have "category": ["BEVERAGES", "LIMONADES"].

We did this because some stakeholder told us that there are some vague plans that a product should be in multiple categories.

Good, problem solved.

However, the problems arise when the first consumer starts using our new service. Remember, we are replacing an existing system!

Consumer: “Hey, I just saw that you return a list of categories. The old system just gave us one! We cannot handle multiple categories.”

Developer: “Oh, no problem. There’s only one. Just take the first one.”

Well, that was a small problem. The bigger problem comes when it’s really time for the new category structure:

Stakeholder: “Hey, do you remember when I told you that we are working on a new category structure?”

Developer: “Yes, of course! We already implemented it!”

Domain Expert: “We decided that every product must have a category tree now! Because some products can be in the main category as well as in of it’s specialized children!”

Developer: “A tree? You said it’s a list? So we did… ah damn… we change it…”

And for the brand? Well, there’s a similar story. Remember that the domain expert told us that the simple brand name (as it is in the current system) should be replaced with a more sophisticated brand object which includes an address and a sub-brand?

Domain Expert: “Hey, do you remember when I told you that we are working on better brand information? With an address and stuff?”

Developer: “Yes, of course! We already implemented it!”

Domain Expert: “We have a brand service now! It takes care of all brand related stuff. You just need to send the brand ID! Isn’t it great?”

Developer: “Brand ID? But we already implemented an address! So… well… we change it…”

So what’s the problem?

The actual problem is about anticipation and knowledge. The domain expert wants to do a good job. So when asked by the developer, he not only presents facts, but also gives some vague outlooks on the future. The developer on the other side takes it for granted and wants to do a good job, too. He wants to be prepared and starts engineering. The software becomes complex, but someday it will pay out! But when this day comes, requirements have changed and the sophisticated solution of the developer still doesn’t fit. All the hard work, complex code and generic modelling has been for nothing.

So the domain expert anticipates that even uncertain information is important information. But this actually leads to weak and unclear requirements. The developer anticipates that he must address every scenario better now than later. This leads to overcomplicated software and abstractions.

Bottom line

So what’s the bottom line? Writing software which can never been changed? Of course not! Software will always change. Actually, it doesn’t matter what the domain expert says. Even if he says that this particular business process will never change - it will! Software must always be written having future changes in mind.

- Writing changeable software means decoupling, because you cannot change a big ball of mud.

- Changeable software means writing tests, because you cannot change if you don’t know if you break it.

- And changeable software means to keep things simple, because you cannot change something you don’t understand.

Having said this, keep your software simple and clean. As less abstraction and anticipation as possible. If you can change it, you can do it when it’s time for.

Best regards, Thomas.